Before we dive into this week's article, I'd like to take a moment to connect with you, my valued readers. Your support through likes and subscriptions has been incredible, and if you haven't subscribed yet, I'd be grateful for your support. I'm also eager to hear your thoughts. What topics interest you most? Your suggestions will help shape future content and strengthen our community. Now, let's get straight to this week's article!

Europe is quietly undergoing a financial revolution that could fundamentally reshape the continent's political future. In 2020, the European Union began borrowing €750 billion collectively, creating shared debt that all member nations are responsible for, yet the EU itself lacks substantial independent tax authority. As these bonds mature, pressure mounts for new EU-level revenue sources that increasingly resemble taxes, even if carefully labeled otherwise. Today we will examine how European bonds are silently pushing the continent toward deeper fiscal integration, potentially creating a federal Europe through financial mechanisms rather than political agreements.

The history of EU bonds

While the EU had limited experience with bond issuance before 2020, mainly through crisis mechanisms during the 2010-2012 sovereign debt crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic marked the beginning of a new era. Earlier programs included the European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism (EFSM), which allowed the Commission to raise up to €60 billion backed by the EU budget, and the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), a temporary vehicle with €440 billion capacity backed by eurozone member guarantees.

In July 2020, EU leaders established the €750 billion NextGenerationEU (NGEU) recovery fund, representing the first time the European Commission borrowed on capital markets at such massive scale. Unlike previous crisis-oriented bonds, these were backed by the entire EU budget and partially distributed as grants rather than loans, creating genuine European debt. As of early 2025, the EU has issued approximately €450 billion in bonds under NGEU, with a current total EU debt load approaching €550 billion when including other programs. This revolutionary approach has signaled a fundamental shift in EU fiscal integration, transforming bonds from exceptional emergency instruments into potentially a permanent part of the EU.

The revenue of the European Commission

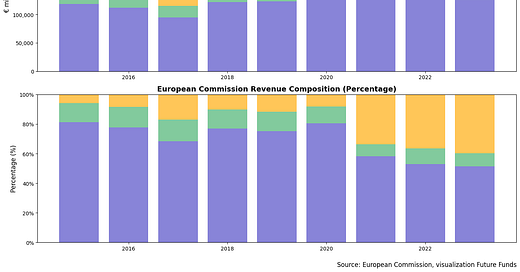

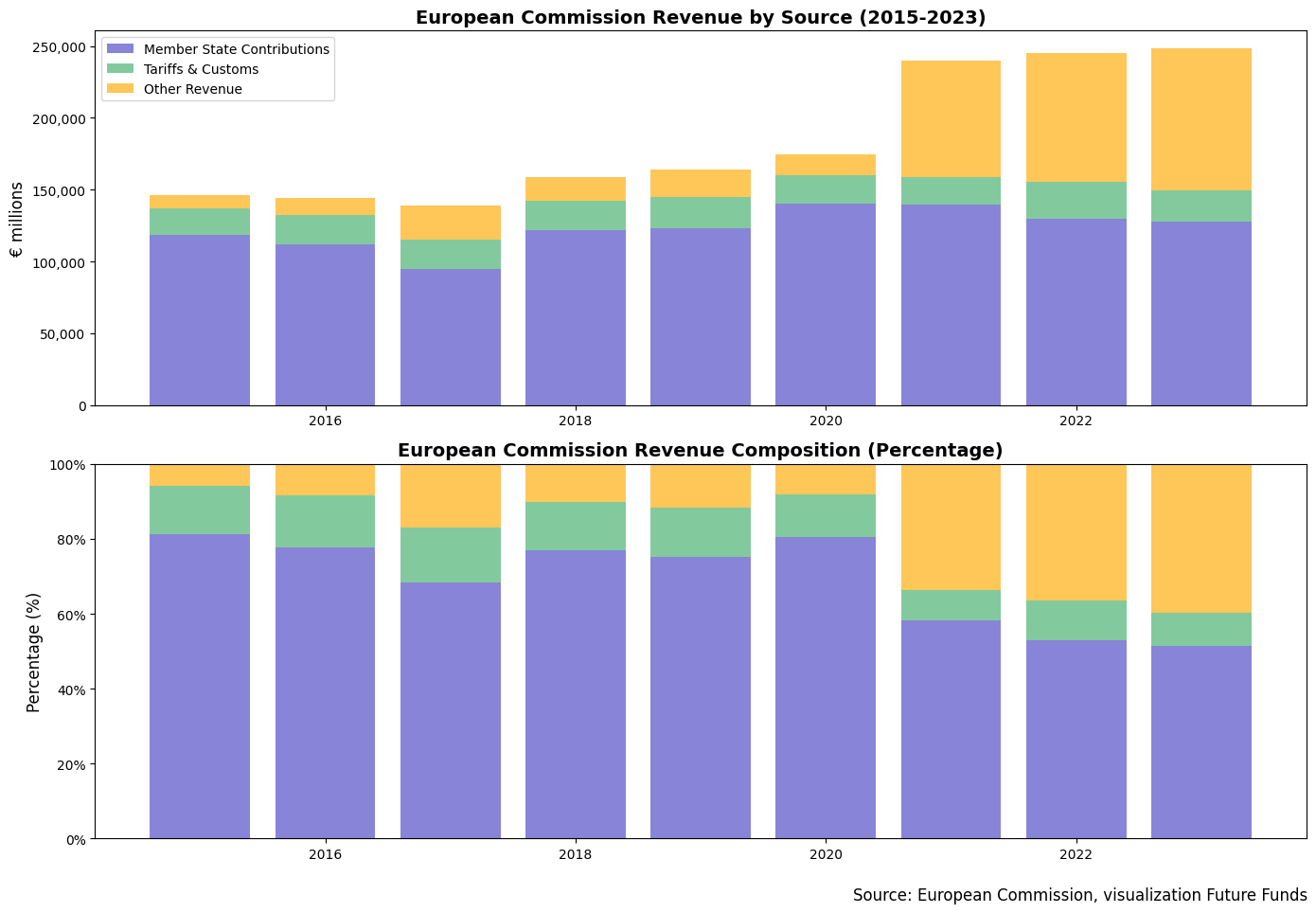

Examining the EU's revenue structure reveals dramatic changes due to its new borrowing activities. As figure 1 shows, total EU revenue grew 70% from €146 billion in 2015 to €248 billion in 2023, with a significant shift in composition.

Member state contributions (purple) remained stable in absolute terms but declined proportionally from 81% to 51% of the budget. Tariffs and customs duties (green) provided a consistent €19-25 billion annually, representing 9-14% of total revenue.

Figure 1

The most notable change in Figure 1 is the surge in "Other Revenue" (yellow) after 2020, jumping from €14 billion (8%) to nearly €99 billion (40%) by 2023, directly coinciding with NextGenerationEU.

Figure 2 breaks down this "Other Revenue" category, comparing pre-COVID (2019) with post-NextGenerationEU (2023). The primary driver is "Budgetary guarantees & borrowing operations," which grew from virtually nothing to €67.6 billion, reflecting proceeds from NextGenerationEU bond issuances.

Figure 2

"Revenue related to Union policies" nearly doubled to €23.4 billion, representing a separate income stream from borrowing activities. This category includes fees paid by non-EU countries to participate in EU programs like Horizon Europe (research), Erasmus+ (education), and the Single Market; contributions for specific policy initiatives; and revenues generated by EU agencies and programs. Unlike borrowing operations, these are genuine revenue sources where external entities pay to access EU services, expertise, or market opportunities.

This fundamental shift in revenue structure, with bond issuance becoming a central financing pillar, raises questions about long-term sustainability. Traditional "own resources" like customs duties are proving insufficient to back this scale of borrowing, creating pressure for new revenue mechanisms to ensure EU bond credibility.

The final implication: a unified Europe

The issuance of common European debt represents a fundamental shift toward deeper European integration. By creating shared liabilities, EU bonds necessitate sustainable revenue streams to service this debt, inevitably forging stronger fiscal ties between member states.

The EU now faces critical choices about developing new income sources. Several options exist, each with different political feasibility:

First, increased member state contributions could cover these liabilities. However, this is unlikely as national governments typically resist directing more of their budgets to Brussels, preferring to maintain control over spending priorities domestically.

Direct EU-wide taxation represents another possibility, but remains politically toxic. The concept of "European taxes" faces strong opposition from both citizens and member states concerned about sovereignty. This approach, while theoretically efficient, lacks the necessary political support.

More promising is the expansion of European tariffs, building upon the existing customs duties framework. The current global trade tensions, particularly with the United States under Trump, provide a convenient justification for implementing protective tariffs. These could be framed as necessary defensive measures rather than revenue-generating mechanisms, making them more politically acceptable.

The European Commission has already proposed several new "own resources", essentially taxes cleverly rebranded for political acceptance. These proposals strategically frame revenue collection as policy implementation rather than taxation.

The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism would tax carbon-intensive imports under the guise of environmental protection. The Digital Levy would target tech giants' revenues, appealing to public frustration with corporate tax avoidance. A Financial Transaction Tax would place minimal fees on securities trades while claiming to curb speculation. The Corporate Tax Component would establish EU-wide minimum rates to prevent internal tax competition.

These mechanisms strategically reframe revenue collection as policy implementation, making them far more popular than direct taxation. They represent the path of least resistance toward expanded EU financial capacity.

The inevitable path towards a European tax

This evolution of financing mechanisms signals an inevitable progression towards a European tax or tariff, whether individual member states welcome it or not. The practical necessities of servicing common debt are pushing Europe toward deeper integration regardless of preferences of its citizens. As European bonds become a permanent part of the financial landscape, the corresponding need for collective revenue systems will follow inevitably.

The NextGenerationEU bonds have crossed a Rubicon: Europe has taken on collective debt that will require collective solutions. We are witnessing the gradual emergence of a more financially unified continent, where member states, willing or not, must develop common fiscal approaches to meet their shared obligations. The exact form of European-level revenue generation remains uncertain, but its necessity is now unavoidable.

The historical pattern of European integration suggests that crises often provide the catalyst for deeper union. The debt crisis gave birth to the banking union; the pandemic has now delivered fiscal integration through the back door of bond issuance. This pattern suggests that the practical requirements of managing shared debt will supersede political resistance to further integration. Whether one celebrates or fights this development, the financial reality points toward a more federal Europe, not through grand constitutional declarations, but through the financial mechanics of servicing common debt.